When 19-year-old Aleysha Ortiz told Hartford City Council members in May that the public school system stole her education, she had to memorize her speech.

Ortiz, who was a senior at Hartford Public High School at the time, wrote the speech using the talk-to-text function on her phone. She listened to it repeatedly to memorize it.

That’s because she was never taught to read or write — despite attending schools in Hartford since she was 6.

Ortiz, who came to Hartford from Puerto Rico with her family when she was young, struggled with language and other challenges along the way. But a confluence of circumstances, apparent apathy and institutional inertia pushed her haphazardly through the school system, according to Ortiz, her attorney and district officials.

Those officials, in statements that her attorney says display “shocking” educational neglect, have acknowledged that Ortiz never received instruction in reading.

Despite this, she received her diploma this spring after improving her grades in high school — with help from the speech-to-text function — and getting on the honor roll. She began her studies at the University of �������� this summer.

Ortiz can’t read even most one-syllable words. The words she can read were memorized during karaoke or from subtitles at the bottom of TV screens and associating the words she saw with what she heard, she said.

“I was pushed through. I was moved from class to class not being taught anything,” Ortiz told The �������� Mirror during a series of interviews. “They stole something from me … I wanted to do more, and I didn’t have the chance to do that.”

Ortiz was diagnosed with a speech impediment and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in early childhood and has been classified as a student with a disability for “as long as I can remember,” she said.

Ortiz also wasn’t taught how to tell time or how to count money. She can barely hold a pencil because of unaddressed issues with hand fatigue and disputes about school-based occupational therapy, she and her attorney said. She learned basic math, like addition, but has no other math skills.

Accommodations in her Individualized Education Plan, which spell out what services students will receive that school year, allowed her to audio-record classes and meetings with school leadership because of her inability to read or write in high school.

In recordings shared with the CT Mirror, made from March through June of this year, district officials acknowledged that in 12 years, Ortiz never received reading instruction or intervention. The CT Mirror also reviewed Ortiz’s educational records, including her recent IEPs and other documents.

“In my review of Aleysha’s IEP, she was never provided reading instruction,” Noreen Trenchard, a special education administrator for the district, said at a May 29 Planning and Placement Team (PPT) meeting. “What is most concerning to me, honestly, at this time, is … with all of that information prior to today, no direct reading instruction was provided for her, and no PPT was requested to add that to an IEP. … That’s very concerning, very, very concerning.”

Trenchard did not respond to a request for comment.

Ortiz said her mother’s ability to advocate for her was limited because of language barriers, insufficient translation services, and because the family didn’t know their legal rights to challenge district decisions.

Ortiz filed for “due process” against the district in late June, which is a legal procedure in special education that’s triggered when families feel their rights were violated.

Ortiz’s lawyer, , said the young woman’s story may be one of the “most shocking cases” of educational neglect she has seen in 24 years.

“It is really shocking, and it should never have happened and shouldn’t be happening,” Spencer said. “Her whole future is going to be impacted.”

Ortiz repeatedly described her special education experience with one word: traumatic.

She said she was unlawfully restrained, spent months in classrooms without a special education teacher or paraeducators, and was ridiculed by untrained staff who would laugh at her.

Her time in Hartford Public Schools was defined by feelings of isolation and loneliness as she sat in the back of classrooms for years and wished she would be able to do what the other kids were doing, she said.

While other students made friends and learned basic math and reading skills, Ortiz said she was stuck tracing letter worksheets on her own from first grade well into her middle school years.

Since first grade, she said, teachers, school leaders and district administrators failed her.

In a recording of a June 6 meeting with Trenchard, the district’s special education administrator, Ortiz can be heard saying she was denied the right to a fair education when teachers didn’t teach her how to write, when disability testing wasn’t done accurately and when she felt shamed by educators after she brought up how her IEP wasn’t being followed correctly.

“People didn’t forget about me — no — people chose not to [educate me]. People chose not to [change] my IEP. People chose not to do this and that and this and that,” Ortiz said at the meeting. “I’m the one paying the consequences, while those people are still getting their checks.”

Ortiz tried to teach herself and make up for the areas her formal education lacked, but through those efforts, the 19-year-old said, she also lost the chance to just be a kid.

“Basically [in high school], I would go to class. I would record and try to memorize everything the teacher said and what I wanted to write. Then, when I went home, I would stay and hear the recordings. I basically went to school two times in one day,” Ortiz said.

“I wanted to join clubs, but I couldn’t do that because I didn’t have the time. … To this day, I’ve never been out to the movie theater with friends, ever,” Ortiz said. “I didn’t have time to have fun. It was either enjoy myself or fail my classes, and maybe if I was more ahead in reading or writing, I would’ve had time [to make friends].”

Ortiz’s story can’t be defined as a student who fell through the cracks — several people knew how her education was being neglected and did nothing, Spencer said.

“She’s had so many teachers. I don’t know how everybody failed her,” Spencer said. “I don’t know how the district could have passed her through. I don’t understand how this happened. It’s negligence, in my opinion.”

The district declined to “speak specifically to student matters,” because of “state and federal legal obligations,” after requests for comment by the CT Mirror, particularly in regards to why it took so long to find a problem with Ortiz’s academic progress and whether officials were aware of similar situations happening with other students in Hartford.

But in a meeting on June 6, Trenchard acknowledged that educators may have violated Ortiz’s IEP, which is a legally binding document under the and outlines the services and accommodations that will make a student with a disability successful in a classroom.

“And truthfully, from what I’ve seen, I see that you didn’t even have an appropriate IEP,” Trenchard said.

“People got to you too late, which has been the story of your life here,” a Hartford Public High School administrator can be heard telling Ortiz in the recording from the meeting on June 6, despite Ortiz saying she had raised concerns for several years and they were never formally addressed.

Ortiz was able to graduate because she had met all her credit requirements, but she says she was only able to “survive” high school through the use of speech-to-text applications and a calculator.

And though limited, the accommodations helped Ortiz become an honor-roll student and led to her acceptance to several colleges, including the University of ��������-Hartford, which she began attending part-time in August.

Ortiz’s success may be unique, but her challenges in the district are not, several current and former staff members from the school district told the CT Mirror.

“I think this happens a lot through Hartford schools,” said a Hartford paraeducator who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation. “I don’t think a lot of kids in Hartford get their services. She’s not the only one. … Any school [in the district], you’ll find kids, even that are not in special ed, that don’t even know how to read and write — they just pass them over.”

“Unfortunately, the way the district runs, it’s short-staffed. It’s fast-paced,” said a social worker who worked with Ortiz in high school and also requested anonymity for fear of retaliation. “While Aleysha is a very sad and touching story, it is one of many in the district that get overlooked.”

Ortiz and her attorney think so too.

“One of the reasons I didn’t drop out was from anger — and knowing that I might not be the only one, but you don’t hear it around,” Ortiz said. “With me, people knew about it and didn’t want to do their job, and knowing this — it must be happening in other places.”

“It’s happening all the time, and it’s not just Hartford,” Spencer said.

Aleysha’s story

At the age of 32, Carmen Cruz decided to migrate from Puerto Rico to the South End of Hartford with three of her four children, including Ortiz, who was 5 at the time, the second-youngest.

Ortiz’s mother declined interview requests, but Ortiz said her family came to the United States because services for students with disabilities were limited in Puerto Rico.

“We heard �������� had the best education and things like that, which is one of the reasons we came to Hartford,” Ortiz said. “We came to get better opportunities.”

In testimony to state lawmakers for more school funding earlier this year, Ortiz described preparing for her first day of first grade at Burr School, when the school educated grades K-8. That day was full of nerves but also tinges of excitement.

Ortiz only spoke Spanish, and learning English with a speech disability would be challenging. But Ortiz said her mother thought she would get the proper services and support to make sure she was successful.

“The first day of school, I was holding my mom’s hand and didn’t want to let go,” she said in the testimony. “I finally did, and I believe it was the biggest mistake of my life. … From the first day, I struggled so much.”

Despite bringing a signed document from the Puerto Rico Department of Education outlining the need for occupational therapy, the service was never provided to Ortiz in Hartford Public Schools, according to her IEP and audio recordings.

For many of her primary school years, Ortiz admits, she struggled with behavioral issues, including throwing things in a classroom, screaming and running away. As she’s grown older, Ortiz said, she realized those behaviors were rooted in anger that manifested from an inability to communicate.

Throughout elementary school, Ortiz was often isolated from classmates and engaged in activities that didn’t pertain to learning, including organizing books, sweeping, resting her head on the desk and drawing pictures in the back of the room, she said. Through fifth grade, the only school work she was assigned was tracing letters on worksheets.

“Instead of teaching me, they would tell me ‘Here, you go play games over there.’ And I’d see the other kids and would get angry,” Ortiz said. “I would just look and stare at the other kids doing their work. … It got to a point where I was the bad kid, and it felt good … because even though I was not like the other kids, at least I was something. And that, for me, was what mattered. I was something to someone [even if it meant getting in trouble].”

Ortiz described several instances where she was removed by security guards by force, including a prone restraint practice where she would be forced onto her stomach and a knee was put on her back to the point that, she said, she couldn’t breathe.

Harford Public Schools did not comment on Ortiz’s allegations, but said, in general, “physical intervention and seclusion are only used as a last resort and emergency intervention, by certified personnel, for students, after other verbal and nonverbal strategies have been attempted and only when the student presents immediate or imminent injury to the student or to others.”

Ortiz said that wasn’t her experience.

“Instead of the security guards trying to have a conversation with me, they would literally just remove me by force,” Ortiz said. “I remember the principal came in, and she was like, ‘That’s not how you do it! That’s not how you do it! Check if she has marks.’ … I was traumatized. … and I was [thinking] ‘Wow, this is how America is?'”

When Ortiz began to learn more English skills in third grade, she said, she developed a relationship with a homeroom teacher, but her communication efforts were shut down after hearing educators discuss how they couldn’t understand her.

When another teacher asked the homeroom teacher if they knew what Ortiz was saying, the homeroom teacher responded, ‘Oh, I don’t understand what she’s saying, I just say yes to whatever she says,’ Ortiz said.

“Just because I’m a special education student doesn’t mean I’m deaf … it’s why I stopped talking,” Ortiz said. “Those things made me feel trapped, insecure and everything. I thought I could talk to someone, then that happened.”

In fifth grade, intervention efforts were short-lived because there wasn’t enough extra staff support, Ortiz said, adding that she didn’t receive her first paraeducator until sixth grade and, even then, she spent most of her middle school career without a special education teacher.

By seventh grade, Ortiz recalled that principals said they “shared custody” of her because she spent more time in the front office than a classroom.

“Instead of sending her to class, the principal had her with her all the time,” the paraeducator told the CT Mirror.

That year, Ortiz was in a classroom “not a lot, maybe four times,” she said.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit at the end of Ortiz’s eighth-grade year.

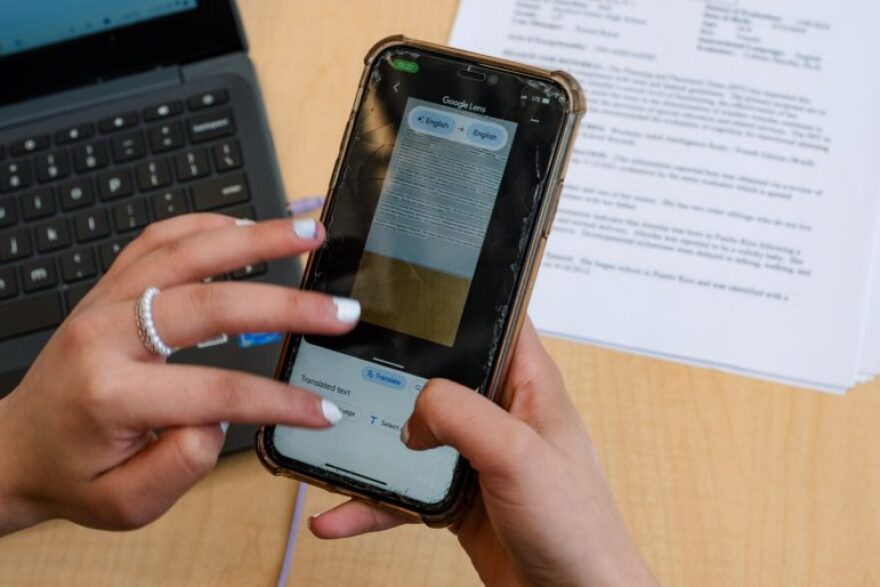

Throughout the summer, preparing for high school, Ortiz went to local libraries and tried to use picture books to teach herself how to read. When she wasn’t successful, she got through online learning during her freshman year with Google Translate, which can scan a photo and read the text out loud.

“The way I did assignments was very difficult. When I was given something to read or write, I would use Google,” Ortiz said. “If the teacher said ‘Aleysha, can you read this aloud?’ … I would turn my computer off and pretend like it died, so I didn’t have to read it. … Or with the camera off, I would repeat [what the translate app said]. That’s literally how I survived ninth grade.”

Sophomore year changed everything.

It was Ortiz’s “first time doing the same work as everybody else,” she said.

“I love learning because I never had the opportunity to learn. People be like, ‘Aleysha, why do you like to go to school all the time?’ And it’s because it’s something new — the amount of times I did the same thing over and over, it’s crazy,” Ortiz said. “Sometimes I do complain, because we learn something new every day and it’s hard to get it, but it’s better than doing the same thing every day.”

Small wins in the classroom built her confidence enough that it allowed her to open up to trusted adults in positions she once felt betrayed by in elementary school. As more people learned her story, a team of staff members gathered behind her and pushed for more services, intervention and support her junior and senior year.

But by then, she was always told any intervention was “too late.”

“Since [my junior year], I told my case manager, I want to learn how to write, and she’d tell me, ‘In college, they don’t do that. They go in there, record and leave, they do the same thing you do,'” Ortiz said. “I’d say ‘Yeah, but I still want to know how to write. It’s my right. I wanted to learn,’ but [I was told] there wasn’t time, and there weren’t teachers to sit down and teach me.”

“There’s a lot of students, and unfortunately, there’s situations like Aleysha, where she has a village behind her, advocating, pushing — and [proper services] still [were] not happening,” the social worker said.

A district’s failure

Ortiz has recorded more than 700 audio files on her phone.

In her last four months in the public school system, more than a dozen of those audio recordings were either PPT meetings, requests for disability testing or administrators reviewing the results of Ortiz’s academic progress with her.

The conversations were often riddled with , with several instances of people speaking over one another or Ortiz leaving the room in tears.

“There was a lot of pushback stating that [the district doesn’t] provide that at the high school level, that they would need to get creative in how they could provide these services to her, and there was always kind of a lingering talk of something would be done, but there was never anything proactive being done,” the social worker said.

Meetings particularly ramped up as Ortiz got closer to graduation and as she was trying to navigate her transition into higher education.

But it always felt like there wasn’t enough time for intervention.

“I feel like right now people are like, ‘Well, she’s graduating,’ and they just move on. They just forget about [what’s happening to me],” Ortiz said in a PPT meeting on May 29. “I’ve been asking, I’ve been doing everything for years and years. I sat here for 12 years. And right now it’s like ‘Well … we should have done this … but we didn’t.'”

One point of contention centered around school-based occupational therapy.

For years, Ortiz had complained of pain in her hand and an inability to hold a pencil for longer than a few minutes. In March, Ortiz’s case manager agreed to consult with an occupational therapist to see what recommendations they had.

But by May 29, district officials declined to have a formal occupational therapy evaluation.

In an emailed statement to the CT Mirror, a spokesperson from Hartford Public Schools said, “If there is no relevant data to support a request for an evaluation, a PPT can determine that a particular type of evaluation is not appropriate at that time.”

“The purpose is to be able to function in a school environment, which Aleysha has been able to do,” a district official said at the May 29 PPT, despite protests from teachers and school staff that Ortiz is only able to perform in a school environment with “incredible difficulty.”

At the meeting, district officials recommended that Ortiz type assignments on a computer going forward.

“People expect me to use a computer for the rest of my life,” Ortiz said.

The underlying concern in all the meetings, in addition to her inability to write, was also the lack of progress in her reading ability.

Ortiz and other staff members repeatedly requested dyslexia testing with the notion that, if she couldn’t receive intervention, then at least having the diagnosis could open the door to more resources after high school.

Those requests were declined by administrators, who instead reviewed previous data, then completed a series of comprehensive testing to “know exactly where we’re at in instruction,” Trenchard said at a meeting on June 13.

In May, Trenchard, the district’s special education administrator, began to review Ortiz’s case. When she went over reading results that were conducted earlier in the school year, she called them “surprising.”

“[The scores] are low low, like they were surprising to me. It would make sense that reading is hard for you, but it looks like things pretty much across the board are hard,” Trenchard said at a meeting on May 20. “You don’t know how to [read, write or do math] because nobody ever taught you. … I wish we met each other earlier … because it bothers me to hear about it and to just see that for years what was missing.”

Trenchard, at a meeting on May 29, said Ortiz’s difficulties in , which are the processes of using letter/sound knowledge to write and read words in a text, could be “symptomatic of dyslexia” but could also be “symptomatic of not having received instruction.”

“And in my review of Aleysha’s IEPs, she was never provided reading instruction,” Trenchard said, adding that she didn’t believe Ortiz was dyslexic because “there are many missing pieces toward even leaning toward that diagnosis.”

Spencer, however, argues that the district violated its legal obligation to provide dyslexia testing because there was a reasonable belief that it could have been an issue.

“If she was showing no reading issues, and all the testing showed she was fine, and she was on grade level, and she just wanted to get the testing — then they could have an argument,” Spencer said. “But, when it’s a suspected area, it must be tested. … There’s no way a reasonable person would have overlooked this.”

Ortiz received a comprehensive reading evaluation on June 6 and scored “very poor” in every category. Ortiz needed to be taught every reading and spelling skill, according to the test results.

And beyond failing to provide basic education, the district may have also failed to provide an appropriate IEP, and with the limited accommodations that were written, they were not consistently implemented or provided, Trenchard said in one of the recordings.

At Ortiz’s last PPT meeting on June 14, just two days before graduation, district officials recommended that she defer her diploma and take 100 hours of reading intervention over the summer at the district’s central office.

Without speaking to Ortiz’s case, Hartford Public Schools told the CT Mirror that recommendations are made “on an individualized basis by the student’s PPT,” and that a student’s exit criteria could be reviewed or revised “up to and including the day of graduation if necessary.”

Ortiz and several of her teachers shared a hesitancy about the deferment plan, especially in regards to uncertainty from the district about who would provide direct instruction to Ortiz if she stayed back amid millions of dollars of budget cuts in the upcoming school year.

“The bigger question is who is doing this? … As of right now, we are working with very minimal staffing, and our special ed staff is doing everything they can, but there’s no one here,” a teacher at the PPT meeting said.

“You can’t require me not to take my diploma and expect me to go along with whatever you say, knowing damn well we don’t have the people here,” Ortiz said at the meeting. “You’re saying we have the teachers training, we have the people here — where are they? If they are here, and they are training, where are they?”

Ortiz was also set to begin a mandatory transition to college program at UConn that ran from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. throughout the summer. The district did not provide any further accommodations or compromise for reading intervention, according to the audio recording of the meeting.

Ortiz ultimately decided to accept her diploma. By the time she had graduated from Hartford Public Schools, she hadn’t been tested for dyslexia and had never received reading intervention.

Systemic shortfalls

At the same time that Ortiz, her advocates and district leaders met about additional accommodations and intervention services, the district also announced a looming for the upcoming school year.

200 special education teachers, 360 paraeducators and 150 counselors, social workers and school psychologists were employed across the district’s schools in 2022-23.

At Hartford Public High School, which Ortiz attended, there were 21 special education teachers, 19 paras and about 15 social workers, counselors and school psychologists in . With over 109 students with disabilities enrolled at the school, social workers could be assigned dozens of cases.

“At the end of the 2022-23 school year, we were short-staffed multiple social workers in the building. Myself, alone, was required to service 50 or more students,” said Ortiz’s former social worker, who added that she ultimately left the district because of the workload.

“[A big part of why I left] comes down to not being able to fully provide children with what they need, and becoming a part of the failure,” she said. “I was part of that team of service providers who didn’t always meet Aleysha where she needed perfectly every month. … There were times I wouldn’t see her for two weeks. … It wasn’t fair to her, but due to the system of the school and the district, we did the best we could, but that’s not the answer we should be giving, especially for students like Aleysha.”

Ortiz was assigned a handful of different social workers during her time at Hartford Public High School because of staffing turnover, the social worker said.

“There’s plenty of students who are kind of slipping through the cracks,” she added.

When asked about student-teacher ratios in special education, Hartford Public Schools said “caseloads are specific to each school,” and depends on “each PPT according to each student’s individualized needs.”

With the expiration of federal COVID-19 relief funds in September, the district cut school staff by 8% by eliminating 229 roles, a majority of which were temporary or non-certified employees like social workers, paraeducators, resource teachers, student engagement specialists and family community school support providers who were hired during the pandemic.

Hartford Public Schools, after its final budget passed in July, lost a total of about 30 counselors, psychologists and social workers.

A spokesperson from the district said that paraeducator staffing has increased from 457 in 2023-24 to 460 in 2024-25, with an increase of 44 special education para positions and a decrease of 41 in all other para positions.

Despite the increase, school staff and education stakeholders say they still anticipate drawbacks in the classroom, including a growing difficulty to provide individualized services and larger classroom sizes for already struggling teachers.

Staffing levels at schools are “disconcerting,” Spencer said.

“They were bad before COVID, but they are really bad right now,” Spencer said. “Schools are not implementing IEPs, are not identifying children, they’re not providing the staff that are required, and it is a real crisis.”

A spokesperson from Hartford Public Schools said that “staff turnover for any position causes a ripple effect for schools, not just special education.”

“Hartford Public Schools is actively working to fill special education vacancies via targeted approaches such as building partnerships with universities, cultivating internal pathways for paraeducators interested in becoming teachers, utilizing social media and attending job fairs,” the spokesperson said.

A from the state Department of Education showed the problem is not just in Hartford but that school staffing shortages are occurring across the state.

Ortiz was front and center in funding advocacy her senior year through letters to the city council, , state Department of Education and a senior capstone project titled “Special Education: A systemic failure.”

“I should have had the help of a special education teacher, a paraprofessional, lessons designed to meet me where I was and challenge me, speech therapy, and occupational therapy. I felt like [no one] cared about my future, because I didn’t receive those supports. I now realize that this was due to a lack of funding and the inability to keep good teachers and staff,” Ortiz wrote to state legislators.

Ortiz told the CT Mirror that she shared her story so her experience doesn’t repeat in other children.

“It’s knowing that more kids are falling through the cracks of the system, and we are still making it seem like everything’s great, that we’re doing better for the next generation, and I always ask ‘When?'” Ortiz said. “The amount of times I would try to look for stories that can relate to me, so I could be like ‘OK, I’m not the only one.’ I would try to do that, I would Google people that went to college and did not know how to read. I couldn’t find anyone. … So maybe if I am the first, and I know I’m not, maybe people can be like, ‘That person made it.'”

.